Getting A Laugh Out of Lou Reed

The strange and enduring afterlife of a great New York artist.

The first time I met Lou Reed, I got him to say things that should have remained unsaid. I know this because he followed me to the door of his publicist’s office, looked me dead in the eye and said with just the slightest tinge of sarcasm, “I’m depending on your good graces to be discreet.”

Inadvertently, I’d goaded him into talking about an ongoing lawsuit with a former manager. I had no intention of writing about it, since the hook for the article was a song cycle he was performing with his longtime frenemy John Cale about their late patron Andy Warhol. But there was something about Lou Reed that made you want to bust his balls, even if you loved his music. Perhaps it was because he had so busted so many balls himself.

“I’ll see what I can do,” I said.

Obsidian dark eyes fixed on me. “How do you say ‘fuck you’ in L.A.?” he asked.

“Trust me,” I said.

Just before I turned away, I thought I saw him smile a little.

Everybody has their own personal Lou Reed. Even the people who hate him or only know him for “Walk on the Wild Side.” He’s the poet laureate of the disillusioned and disaffected. There’s one or two like him in every crowd and every classroom, muttering something that unnerves the teachers and cheerleaders of the world.

Of course, being the voice of the malcontents is not going to propel you to the top of the charts very often, but lately there’s been a lot written about Reed. The occasion is the upcoming tenth anniversary of his death - at the unlikely age of 71 - and the publication of Will Hermes’s dense biography Lou Reed: The King of New York. The New Yorker, The New Republic, the Atlantic, and countless online outlets have weighed in on his dark legacy. Some have embraced him as an icon of transgressiveness, while duly noting he could be a mean son of a bitch. Others have claimed him as an emblem of the LGBTQ community, despite the fact that he enjoyed two long-term marriage/relationships to women. And some, like Hermes, have noted that a personality as complex and contradictory as Reed’s cannot easily be defined under one heading.

It took me around to come around to him. Even as a teenage misfit, I was nonplussed at first by the black eyeshadow, nail polish and frankly lazy writing he was doing in the 70s. I was more drawn to the mas macho deranged avant-garde Welsh-cowboy stylings of his former bandmate John Cale:

But then I had my Lou Reed moment. I was alone and downhearted, and a long way from home. And drunk. I had a copy of a record called 1969: The Velvet Underground Live that I’d picked up in a downtown discount bin and had never opened. But as soon as I dropped the needle on to the vinyl, I was no longer alone anymore.

“We saw your Cowboys today and they never even let Philadelphia have the ball for a minute,” Reed teases the audience in his Brooklyn-Long Island accent, after good-naturedly busting their collective balls for living in Texas. “It was 42 to 7 by the half. It was ridiculous. You should give other people just a little chance. In football anyway.”

It was like hearing from an older, wised-up friend from the city. “You should give other people just a little chance.” Even if they’re involved felonies, shooting smack, having sex in unconventional configurations, or so caught up in their own sorrows that they can barely speak to anyone else. That was my entry point. I was finally ready to hear the songs like “Waiting For The Man,” “Heroin,” “Pale Blue Eyes,” “Lisa Says,” and “I’ll Be Your Mirror,” because I could hear the New York writer’s voice inside them. I’d read about Reed being obsessed with decadence and nihilism. Now I understood his songs were suffused in equal amounts by empathy and compassion. And that division, born of a divided soul, torn between violent emotion and tenderness, has rarely been expressed as artfully and memorably in the world of pop and rock.

It was easy to lose track of the man’s art over the years. There were some crummy solo records. There were also some good ones, but critics were often grudging toward Reed – perhaps because they believed he was cut from the same cloth as them. Occasional appalling public performances didn’t help. I was at a Bottom Line show in 1979 where he berated his record company president from the stage (“Clive, you can suck my dick!” was one of the milder remarks) and then announced he would be performing a suite of songs recorded for his previous label. When I went to the bathroom afterwards, a label vice-president staggered in, looking stunned.

“Hey, what did you guys think of what Lou just did?” he asked woundedly.

The guys at the urinals roared their approval and laughed like they were celebrating a Rangers victory.

When I asked Reed about the show ten years later, he shook his head. “I was just being a drunk,” he said. “A garden-variety drunk.”

He was a tricky guy to interview, at first. It was Lou Reed, so you don’t expect any goddamn ray of sunshine. But he wasn’t exactly unfriendly. His answers just seemed a little out of synch with my questions, like in an old Bob and Ray routine.

But something happened when I switched the tape recorder off - after a second session, which I was probably only invited to because I knew the L.A. punchline). As I turned to leave, I asked him, “So which of your records from the 1970s do you like?”

He lit a cigarette, squinted up thoughtfully at the ceiling, and color flooded into a face that had been stone-gray until then.

“None of them.” He let out a dragon of smoke.

“None of them?”

“None of them.” He sighed and let his shoulders drop a little. “I mean, I know what I was trying to do sometimes. But I didn’t always get there.”

Up until that moment, he’d been looking at his watch, letting me know that every second was borrowed time. But he relaxed and became a completely different presence. He laughed and talked about the Velvet Underground opening for Shirley Ellis who did “The Name Game” (“Yeah, ‘Banana-na-na fo-fana.’ It’s hard to believe that really happened.”) He admitted it was disappointing to listen to some of his old records and painful to recall the experiences that caused him to write some of his most famous songs. “I was doing ‘Satellite of Love’ the other night and I suddenly remembered who it was about.” He mimed playing guitar. “I mean, most of the time, you’re just blasting away, and then it hit me that it was about something real and it was, like, have you ever felt jealous? I mean, really, really jealous? It all came back to me right there.”

I realized that until I shut off the tape recorder, he had been sustaining a performance as Lou Reed, and it cost him something.

There’s a term in psychiatry and journalism known as “the doorknob revelation.” It generally means you should listen very careful to the last thing that somebody says to you. Because they may be dropping their guard because they think the coast is almost clear. I’m not saying the nice, self-effacing guy I spoke to was the one real Lou Reed. But I believe it was as real as any other Lous, including the ones who were senselessly cruel and hurt people who loved him. Or maybe that was just the Lou Reed I wanted to meet.

But so what? Everyone hears the song and the singer they want to hear. For you, it might be Bob Dylan. For your daughter, it might be Taylor Swift. But you take what you need from their music and maybe it gives you what you need to get through the day. Or in Lou Reed’s case, the night that seems like it’s never going to end.

So what I took away from Lou Reed was this: It doesn’t matter what you do at your highest point. It doesn’t matter what you do at your lowest point. It only matters that you go on. Because you never know what will change. One of my favorite stories from Reed’s final days came from Laurie Anderson. The doctors told the couple there were no more options for Reed’s cancer treatment. But Mr. I Don’t Care, who’d been writing songs about “closing in on death” since at least his early 20s, only heard the word “options.”

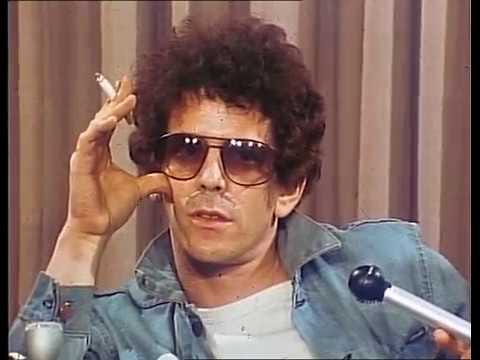

Here he is about, little over a year before his passing, doing one of his most famous songs,

After I turned off the tape recorder that day, we spoke for about an hour. It’s entirely possible that John Cale was waiting in a rehearsal room down the hall and perhaps not enjoying the afternoon as much. The talk turned to writing and I asked Reed why he had never produced a book of his own. After all, he’d studied with the great poet Delmore Schwartz at Syracuse University and had a well-deserved reputation as the most literate of rock and rollers. He said he was trying but it wasn’t easy. And he still had a lot of lyrics to write.

“Yeah, I get it,” I said. “But some of the words seem like they could already be in a serious Jewish-American novel. Like something by Saul Bellow or Philip Roth.”

“’Nah.” He curled his lip. “They’re just rock and roll lyrics.”

“’What do you do with your pragmatic passions,’” I quoted his own words back to him. “’With your classically neurotic style? How do you deal with your vague self-comprehensions? What do you do when you lie?’”

He stared at me for a beat and then laughed as the elevators doors opened to take me down.

“Stop it,” he said. “You’re killin’ me.”

Then he lived another 25 years.

Amazing anecdotes and insights, Peter. He was definitely at war with himself a lot until he found Tai Chi (!?).